Martyr! (A book review?)

This is going to be a book review, I swear. I’m going to get to it, but first let me say: I don’t know if I’ve ever even read a real book review, so if you’re looking for something straight-ahead, maybe go somewhere else. For as bookish and literary the English degree and the blog may make me seem, I feel the imposter syndrome creep in constantly whenever it comes to talking about reading. Before studying English, I wasn’t so much a bookworm – I mostly just figured out what my favorite songwriters read and tried to find what inspired them.

Choosing to study English was mostly a self-serving decision, motivated by a desire to keep finding those sparks to fuel my own creative pursuits. Has this decision gone to serve my LinkedIn profile? Perhaps not, but we’re trying to get those basses covered in the meantime. But enough about me, let’s get into Martyr! a novel by Kaveh Akbar.

Actually, a bit more about me. So, I got married this month! Yes, thank you, thank you. It was perfect, many thanks to everyone who helped make the wedding so memorable. But anyway, I needed a book to read for the honeymoon, so I went to who I always go to when I need a parasocial book recommendation: Jack Edwards – a great bookToker and YouTuber. In a long list of books he recommended, Martyr! gripped me even in passing.

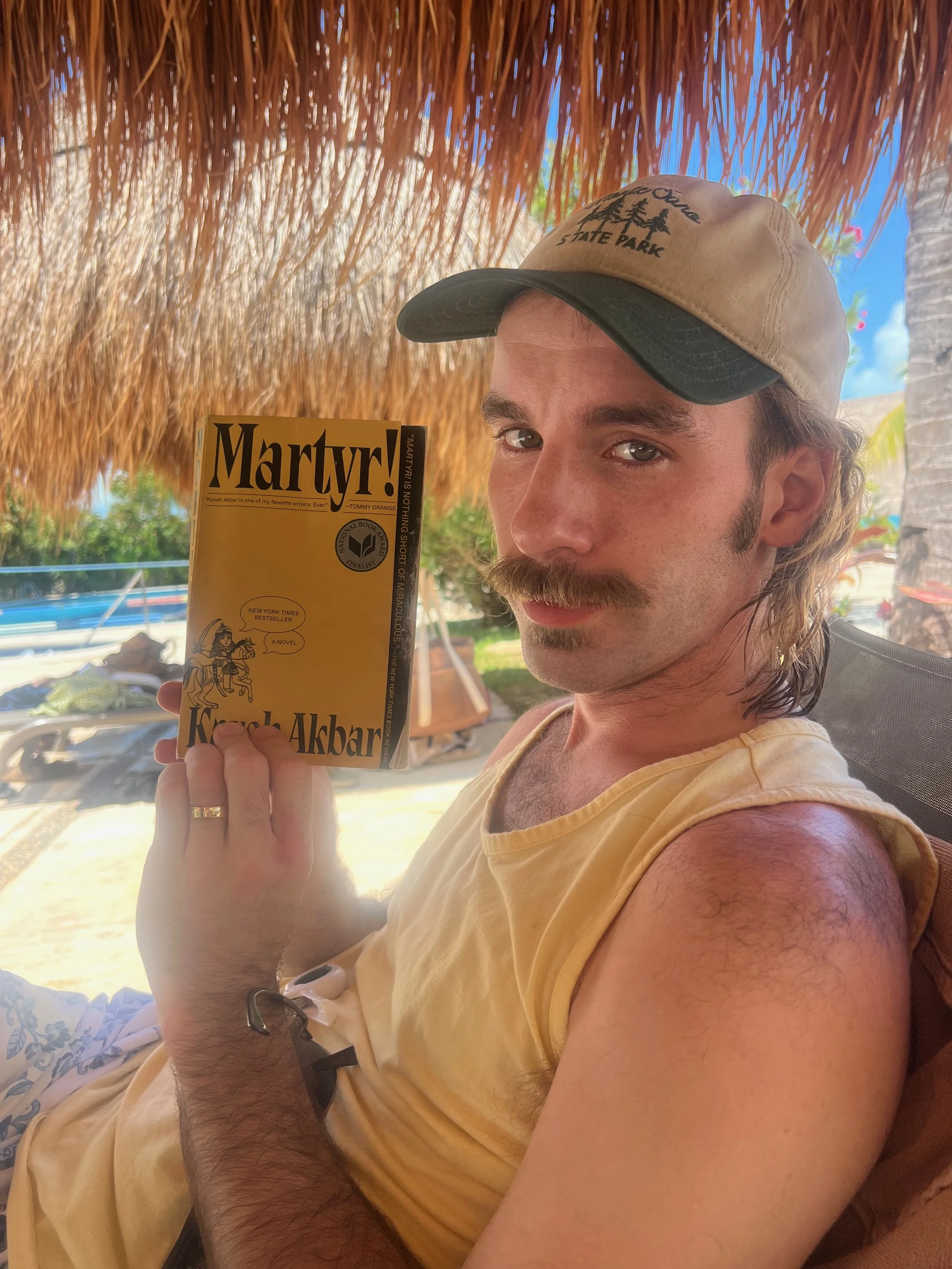

Martyr! is about an Iranian-American poet and addict named Cyrus Shams, but the novel doesn’t just tell the story of his life, the reader also gets the perspective of his friends and family as the narrator shifts from chapter to chapter. This and the hybrid form of the novel, where the author inserts sections of Cyrus’s poetry make it a real page-turner, perfectly suited for fractured attention spans. If you want your fiction to completely wreck you emotionally, this book is absolutely for you. If you don’t believe me, here’s a picture of me crying in paradise because of the emotional abuse this author inflicted upon me.

My tank top matches the book :)

One usually does not become an addict/poet through of an easy life, and Cyrus is no exception. When he was less than a year old, his mother was killed in the tragedy of Iran Air Flight 655. A true incident wherein USS Vincennes mistakenly shot down a commercial airliner flying from Tehran to Dubai, killing nearly 300 people.

This catastrophe shapes Cyrus and his father, Ali, in the way that only the worst kind of grief can. Overcome with rage and an inability to carry on with his life in war-torn Iran, Ali moves him and his son to rural Indiana where he takes a job working on an industrial chicken plant.

The early loss in Cyrus’s life leaves an unshakable obsession with death which later develops into an obsession of martyrs. Now, one thing that I absolutely love about the author’s writing is how much self-awareness he passes onto each character’s own narrative as the perspectives shift. Cyrus eventually turns this obsession with martyrs into a collection of poems, and he jokes throughout the text that if the FBI finds out about an Iranian man whose mother was killed by the U.S. government and is writing a manifesto obsessed with martyrs, it might get him into some hot water.

The protagonist’s Persian identity is extremely consequential to the novel’s unique voice, as Cyrus’s frequent philosophical musings about death, religion, and meaning (topics often philosophically mused over) are tackled from a cultural perspective that’s often overshadowed. That novelty is perfectly balanced by how modern and conversational the prose feels.

Akbar brings a level of thought and insight to this text that reminds me of being around the kind of people that are so smart that you kind of can’t help but be in awe of how they talk about everyday things: “For as long as he could remember, Cyrus had thought it unimaginably strange, the body's need to recharge nightly. The way sleep happened not as a fact like swallowing or using the bathroom, but as a faith. People pretended to be asleep, trusting eventually their pretending would morph into the real thing. It was a lie you practiced nightly or, if not a lie, at least a performance. And while performance did not necessarily void sincerity, it certainly changed it. The speech you practiced in front of the mirror was always different than the one you ended up giving. Nothing else worked this way, insisting upon pretending. You didn't sit in front of a plate of rice, pantomiming swallowing in order to take the tiny grains into your stomach. Sleep alone demanded that embarrassing recital.” See what I mean?

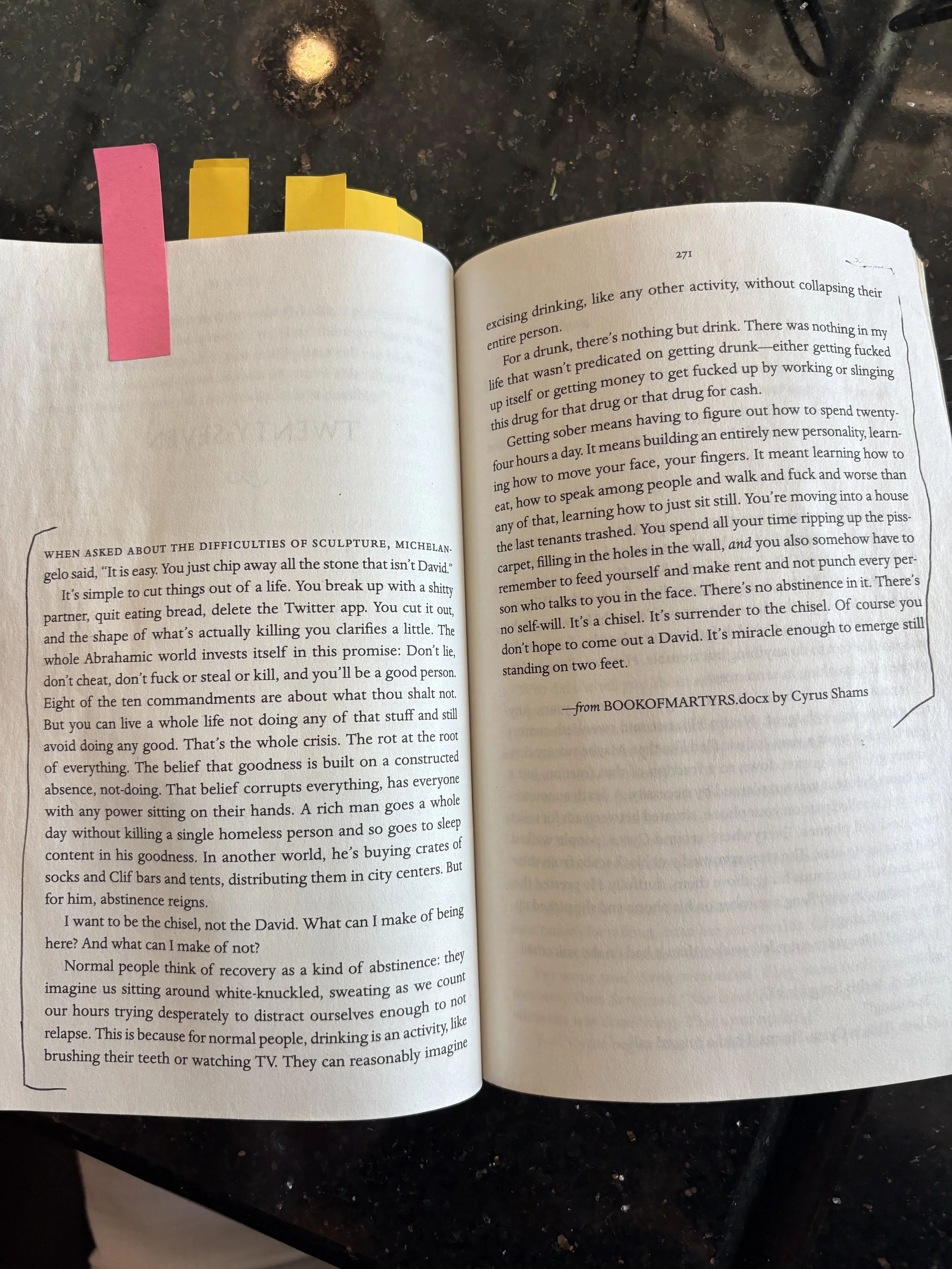

Insomnia is one of the many things that drives Cyrus to drugs and alcohol, and his relationship with them and sobriety is seen from both sides of the bridge, as parts of the novel take place while he’s using and others while he’s in recovery. His ability to write and manage his trauma and addiction constantly hang in the balance, “Before getting sober, Cyrus didn’t write so much as he drank about writing.” After years of kind of just drifting post-grad, the story’s catalyst occurs when Cyrus’s friends tell him about an art exhibition happening in Brooklyn.

"Internationally renowned visual artist Orkideh presents her final installation, DEATH-SPEAK. Visitors will be invited to speak with the artist during the final weeks and days of her life, which she will spend onsite at the museum. No appointments necessary. Opening Jan 2nd." Captivated by the idea of being able to speak with someone literally at death’s door, Cyrus deicides its exactly the kind of spark he needs.

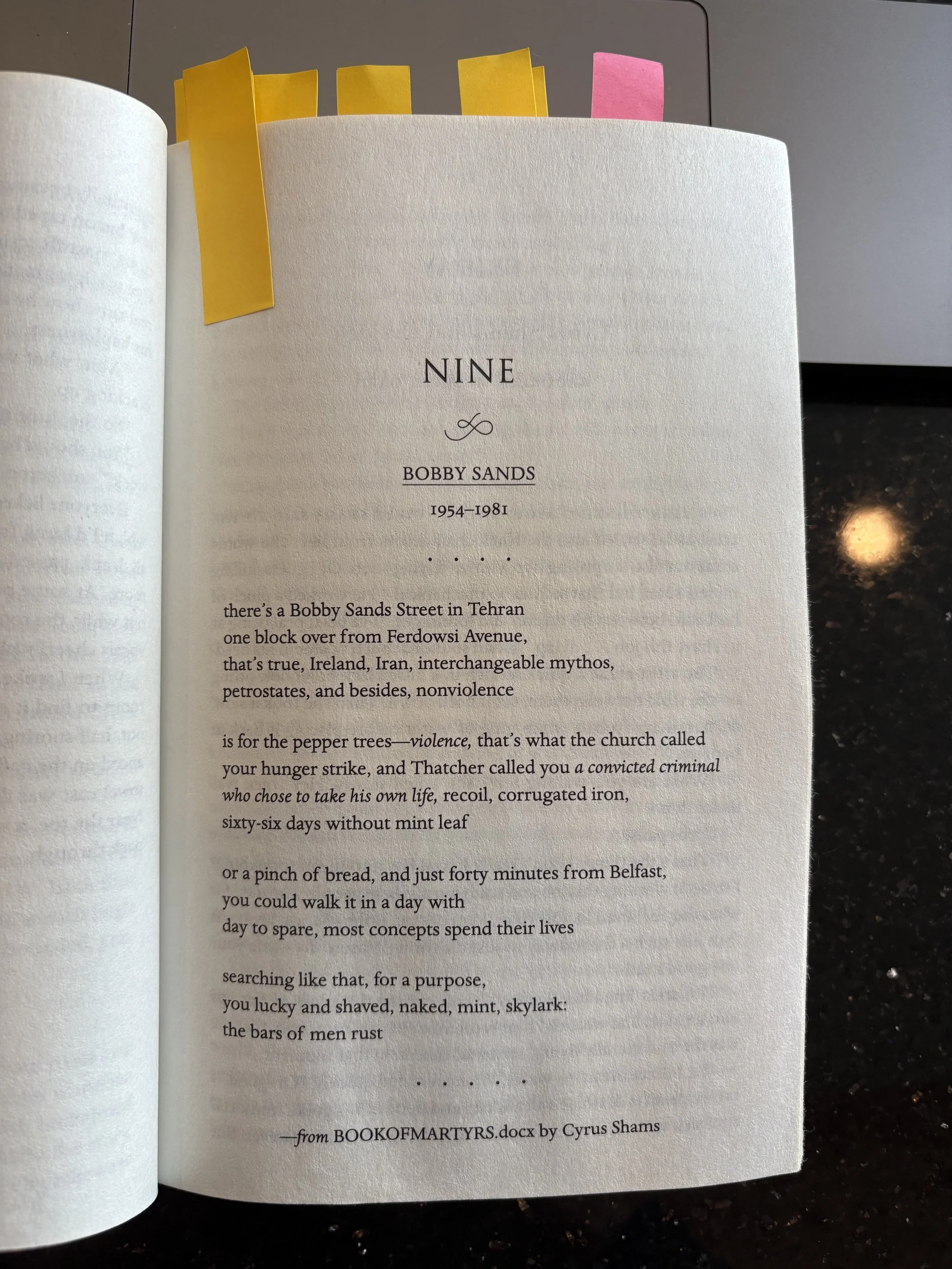

So, Cyrus travels to New York, and along the way the reader is treated to what will become the poems that form his collection as caesuras between the chapters. Further fueling the meta-ness of the novel, each of the poems are told from a different martyr’s perspective, some of these being historical martyrs like Bobby Sands and Hypatia of Alexander, while other poems are told from the voice of personal martyrs, like his mother and Uncle Arash.

Cyrus’s Uncle Arash is one of the most tragic figures in the story. Arash is a veteran of the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s, and he held a very unusual position in the army. His job was to garner a black cloak on horseback with a flashlight, illuminating his head like a halo and ride around the no-man’s-land of dying men who’d been maimed and gassed. Arash played the angel of death, giving his men the courage to die honorably for God. Unsurprisingly, this leaves Arash with a lifetime of PTSD, and the chapters told from his perspective are some of the most gut-wrenching.

Like his uncle, Cyrus’s job also asks him to be an actor in the ritual of death. A few times a week, he goes to his local hospital and works as a medical actor, pretending to be family members of those who have died to train doctors in residence in how to deliver such sensitive news. Cyrus approaches the job with almost psychotic irreverence and takes out his trauma on the captive doctors.

This dynamic must give Cyrus the strangest dose of double survivor’s guilt, as he has to recon with playing in these hypothetical tragedies where he’s the one left behind. Then at the same time, he’s playing a role in deaths that aren’t his just like his uncle Arash, but everything about Cyrus’s role is manufactured, while the deaths for which Arash acts haunt him for the rest of his life.

It’s heavy stuff, man.

One of the parts of the book that resonated the most with me was how Cyrus talks about faith and belief. While Cyrus is a self-described agnostic in the book, this comes in conflict with his obsession with martyrs and how inherent the meaning of their death becomes in the act of becoming a martyr. For Cyrus, its less about the devotion to whatever God or purpose your death honors, but it’s more of an envy for the purpose and certainty the martyr’s death provides. Cyrus’s poem for Bobby Sands, a member of the IRA who died in a hunger strike, speaks to his envy of purpose in a martyr’s death.

I mentioned earlier how much I loved the intersection of the author’s Muslim heritage, modern conversational style juxtaposing the heady, philosophical subject matter and how much it gives the text such a singular voice. There’s something about how Cyrus speaks about his distance from religion from a uniquely Muslim perspective that was extremely refreshing for me. Maybe its how oversaturated the discourse of agnosticism is with former Christian voices, or it’s just how good of a writer Kevah Akbar is (probably some of both), but every time the author depicted cosmic uncertainty and the hubris of belief, it just felt so fresh.

This book ripped me apart. Have you ever cried in a cabana in Mexico while Pitbull was playing? Exactly. I’m the only guy that’s ever happened to, all thanks to Kevah Akbar. I’m so serious, y’all.

For how heavy the subject matter may seem with all the death and whatnot, this book is so well balanced by Akbar’s wit and relatable misanthropy.

I clearly don’t know how to write or approach the tone of a book review, so I’ll leave you with this. If you are looking for something that is going to take over your life for a week or two and take you on a journey where you’ll make some very good friends just to watch them make some very poor decisions and ultimately break your heart like an ill-defined situationship, please read this book so I have someone to nerd out with.

Good to be back,

5/18/25

James