XML: As basic as it gets

An xml guide for non-techy tech writers

This is the ultimate XML guide for the least techie of future tech writers. I am someone who, before learning XML, had zero coding experience. The tech jargon surrounding XML was meaningless to me, and as an English-Lit major I’ve always had a tough time with STEM.

The aim of this XML guide is to cut through the jargon and to try to eliminate the confusion and intimidation you might be feeling while learning XML. Many of the resources I relied on when learning XML left me with countless questions because of how much the instructional content relied on unexplained jargon. Here, it all gets explained in as basic of terms as it gets.

What is XML?

When defining what XML is, even leaders in online programming education, like W3Schools, explain it clearly but often with vague and abstract comparisons.

“XML stands for eXtensible Markup Language”

Ignoring the fact that X is used to abbreviate a letter that starts with E, Let’s continue.

“XML is a markup language much like HTML”

When I first read this, I thought, “I don’t know what a ‘markup language’ language is, and what even is HTML?

A markup language, to put it simply, is a set of symbols (code) that tell a computer how to control the structure and layout of some kind of text document. The most used and well known markup language is HTML, which is used to design websites on the internet.

HTML and XML are often used in tandem, but they have different roles. HTML controls how things look on a website, while XML deals with telling the computer what the actual data is and how to understand it. Think of HTML like a bulletin board, displaying information, while XML is like the filing cabinet where all the information was stored and categorized before it was displayed by HTML.

But wait, what does the “markup” part of it mean?

Much of the language used to describe XML comes from publishing and editorial traditions. The term “markup” comes from the old publishing world. Editors would “mark up” manuscripts with instructions like “italicize this” or “print this in the margin.” Computer programmers borrowed the word. Let’s see the next W3School's definition.

“XML was designed to store and transport data”

By “store,” they mean that XML decides what certain data is and how it should be categorized. Transport literally means moving data between systems. In this way, XML is like a cargo ship. Many more metaphors to come.

“XML was designed to be self-descriptive”

This means that in XML, the data carries information about what it is and what it means, not just the raw values. Lastly, W3C says:

“XML is a W3C Recommendation”

This just means that W3C has deemed XML a universally accepted and approved markup language, like an FDA certification for a food or drug.

W3C (World Wide Web Consortium) is the organization that sets standards and guidelines for how the World Wide Web is developed.

Now that we understand a bit more about what XML is, let’s start to unpack how to use it yourself.

The Basics of Writing XML

Tags

Let’s start by talking about tags. In XML, a tag looks like this: <title> or </title>. The opening tag (<title>) starts the body of an XML document, and the closing tag (</title>) ends it.

Tags are like labels on a box; they tell you what’s inside. They are a part of a bigger concept in XML called an element, which will be explained shortly.

To the computer, tags are like definitions for the data.

Rules for Tags

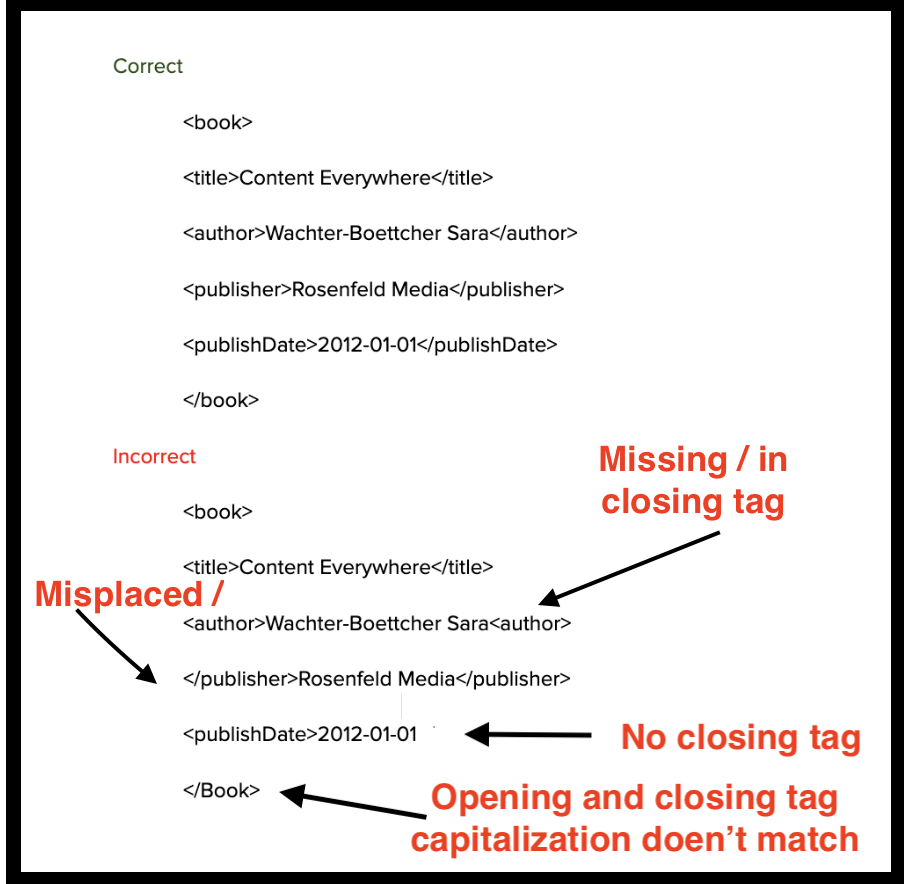

When writing in XML, it is essential to follow the many rules and standards. Here are some of the rules for tags.

Tags have to be surrounded by angle brackets <TheseThings>, which mark the boundaries of a tag.

Tags are always written in pairs. You must start with your opening tag; all your data comes after this.

Then, after all the data has been included, you must punctuate the data with an almost identical closing tag.

I say almost identical because the word within the tag, itself, must match in spelling and case sensitivity, but the closing tag has to be preceded by a forward slash.

The forward slash in a closing tag tells the parser that this tag ends an element rather than starting a new one.

Here is an example: <song>Rock n Roll McDonalds</song>

Another rule is your tag name cannot have any spaces. In the data between the tags, spaces are fine.

Elements

Earlier, I mentioned how a tag is a part of a bigger concept known as an element. These are commonly referred to as the building blocks of XML.

When you combine an opening tag with a closing tag, and put some data in the middle, you have an element.

Here is an example of what an element looks like in XML.

<name>Jar Jar Binks</name>

This works because the element has an opening tag (<name>), a closing tag (</name), and some content (Jar Jar Binks).

Now that we’ve got the basics of simple elements down, let’s learn how to work with multiple elements.

Nesting & Parent-Child Elements:

If you hadn’t noticed already, analogies and metaphors are very common when explaining the ins and outs of XML. A favorite of mine is when they’re compared to Russian nesting dolls.

Think of the root element as the largest doll, and every other element that is enclosed within it are child elements. Any element that has a sub element is called a parent element.

To take the analogy even further, the term nesting is used to describe how these elements fit into one another.

It is important to ensure your elements do not overlap, which is when two or more elements partially cover the same content but don’t nest cleanly inside each other, blurring their boundaries. This means the end tag of an element must have the same name as its matching start tag.

Every XML document should contain a Root Element.

Think of the root element as the root of an upside down tree or as the largest nesting doll.

Each document contains only one root element that contains everything else. In the following example, the root element is <song>.

Here are some longer examples. The second has even more nesting issues:

Before moving on, let’s cover two more minor points about elements.

Empty (self-closing elements)

Sometimes elements don’t need content but still serve a structural purpose.

Here is a very practical example:

<linebreak />

XML allows this shorthand instead of writing <linebreak></linebreak>.

Mixed Content

Elements are not always all text. You can also have mixed content, meaning elements can contain both text and child elements.

Here is an example from a recipe:

<Instructions>

Heat the <ingredient qty="1 cup">milk</ingredient> until it begins to steam.

</Instructions>

Here the <ingredient> element is adding semantic meaning to the word milk by identifying it as a structured ingredient and associating it with metadata (like the quantity).

Mixed content is useful because it allows structured elements to appear inside natural sentences, giving parsers proper structure for processing data, while still remaining readable for humans.

Attributes

Sometimes we deal with data that is important for the computer, but we don’t necessarily want users interacting with it. Oftentimes these are ID numbers or other data points used strictly for sorting and categorizing.

This is when attributes are often used. They allow us to give data extra specificity, without affecting how the data is presented.

Think of an attribute like a sticky note you’d put on a box to give more detail about what’s inside.

Here is an example of an element with an attribute:

<character id="17546"> <name>Ahsoka Tano</name> </character>

Attributes are written within the tag. There are two parts of an attribute, the name and the value.

Name – what the attribute is called.

Example: id, type, lang.Value – the data assigned to that attribute, always enclosed in quotes. Single or double quotes are fine as long as they are straight and they match.

Correct examples:"123" "book", "en".

Incorrect examples: “123” 'book”, 'en".

Well Formed vs. Valid

When an XML document follows all of the rules, it is called being “well formed.”

To quickly review all of the rules of proper XML syntax:

XML documents must have a root element

XML elements must have a closing tag

XML tags are case sensitive

XML elements must be properly nested

XML attribute values must be quoted

If your XML document meets all of these requirements, congrats!!!!!! It is well formed.

As good as that sounds, this is not the same as an XML document being “valid.”

A "valid" XML document must be well formed. In addition, it must conform to a document type definition or a schema.

DTDs and Schemas

Remember earlier when I said that XML was designed to be self-descriptive?

This means that all of the tags don’t have built-in meaning the way they do in HTML. Their meaning comes from the names we give them and the rules we set for them. These names and rules are often defined in a Document Type Definition (DTD) or Schema, which is essentially a rule book.

DTDs and Schemas fill the same role, each have their strengths and weaknesses.

XML DTD: (Document Type Definition)

An XML document validated against a DTD is both "Well Formed" and "Valid".

The purpose of a DTD is to define the structure of an XML document. It defines the structure with a list of legal elements.

Internal vs external DTD

You have the option when writing a DTD to either use an external DTD or an internal DTD.

An internal DTD is better for very simple projects. When working with data that is self-contained and doesn’t dictate standards and rules of multiple XML documents, an internal DTD is usually the way to go.

When you’re dealing with a lot of XML documents, it’s better to use an external DTD because then many different documents can reference a single DTD, making changes is much easier and more efficient.

Where is the DTD in an XML document?

The DTD will appear at the top of the document, before the body of the document.

What does a DTD look like?

<!DOCTYPE catalog [

<!ELEMENT catalog (book+)>

<!ELEMENT book (title, author+, publisher, publishDate, pages, isbn13, price)>

<!ELEMENT title (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT author (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT publisher (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT publishDate (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT pages (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT isbn13 (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT price (#PCDATA)>

]>

What does all of this mean?

!DOCTYPE book defines that the root element of the document is catalog

!ELEMENT catalog (book+)> tells us that the catalog element must contain one or more book elements

<!ELEMENT book element must contain the elements title, author, publisher, publishDate, pages, isbn13, price

Every line after that defines each element to be of type "#PCDATA.”

When you define an element as containing #PCDATA, you’re telling the parser: “This element can contain text.”

XML Schema

An XML Schema is an alternative to a DTD. Both have their advantages and disadvantages that will be covered later.

A schema describes the structure of an XML document, just like a DTD.

An XML document with correct syntax is called "Well Formed". An XML document validated against an XML Schema is both "Well Formed" and "Valid,” just like a DTD.

XML Schema is commonly known as XML Schema Definition (XSD). It is used to describe and validate the structure and the content of XML data.

XML schema defines the elements, attributes and data types. Schema element supports Namespaces.

Namespaces

An XML namespace is a way to avoid naming conflicts in XML documents when different vocabularies (sets of element/attribute names) are mixed together.

If you’re making an XML document and one element name is being used to refer to two different things, a schema will allow you to differentiate these two terms.

For example, if you’re using the element name <table> in two different ways, one describing a piece of furniture and one describing a data grid, the XML parser won’t know which “table” you mean.

This is where namespaces are useful. They let you identify elements and attributes by associating them with a URI (uniform resource identifier).

Namespaces are defined with an XML attribute.

<house xmlns:furn="http://example.com/furniture" xmlns:db="http://example.com/database">

furn:tablefurn:legWood</furn:leg>

</furn:table>

db:tabledb:rowRow 1</db:row>

</db:table> '

</house>

Here:

furn:table comes from the furniture namespace.

db:table comes from the database namespace.

The prefixes (furn,db) are just shortcuts — the real identity comes from the URIs.

Problem solved

Now, in the XML body, when differentiating between the two kinds of table, use furn:table for the furniture and db:table for the database.

Where is the Schema in an XML document?

Just like with an external DTD, the XML document will point to the schema, housed elsewhere.

What does an XML schema look like?

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<xs:schema xmlns:xs="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema">

<xs:element name="catalog">

<xs:complexType>

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name="book" maxOccurs="unbounded">

<xs:complexType>

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name="title" type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="author" type="xs:string"/

maxOccurs="unbounded"/>

<xs:element name="publisher" type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="publishDate" type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="pages" type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="isbn13" type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="price" type="xs:string"/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

</xs:element>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

</xs:element>

</xs:schema>

When to Use a DTD/Schema?

XML users are divided on whether DTDs or Schemas are superior. Both have their advantages and disadvantages.

DTD Advantages

DTDs are simpler, easier to learn and write.

DTDs were developed before schemas, so they are supported by nearly all XML parsers.

DTDs are typically smaller files, making them faster to parse in most cases.

DTDs are easier for humans to read.

DTD Disadvantages

DTDs have limited data types, meaning you can’t enforce numeric ranges, dates, etc.

DTDs were designed before XML namespaces, so handling multiple vocabularies is clunky.

DTDs don’t follow XML syntax. Yes, as strange as it sounds. DTDs use their own declaration language, making it inconsistent with XML syntax itself.

Schema Advantages

Schemas have built in support for integers, dates, decimals, etc.

Schemas works seamlessly with XML namespaces, making it better for complex vocabulary.

Schemas are valid XML. This just means that the same syntax and rules are followed for writing schemas as the rest of an XML document.

Schemas have become the industry standard. Using a schema means you’re more likely following common practice.

Schema Disadvantages

Schemas are much more complex and harder to learn.

Schemas can take longer to validate because of how deep the rules are.

Schemas are much harder for humans to read.

References

In XML, a tool that is often used are references, which are basically short hands or abbreviations.

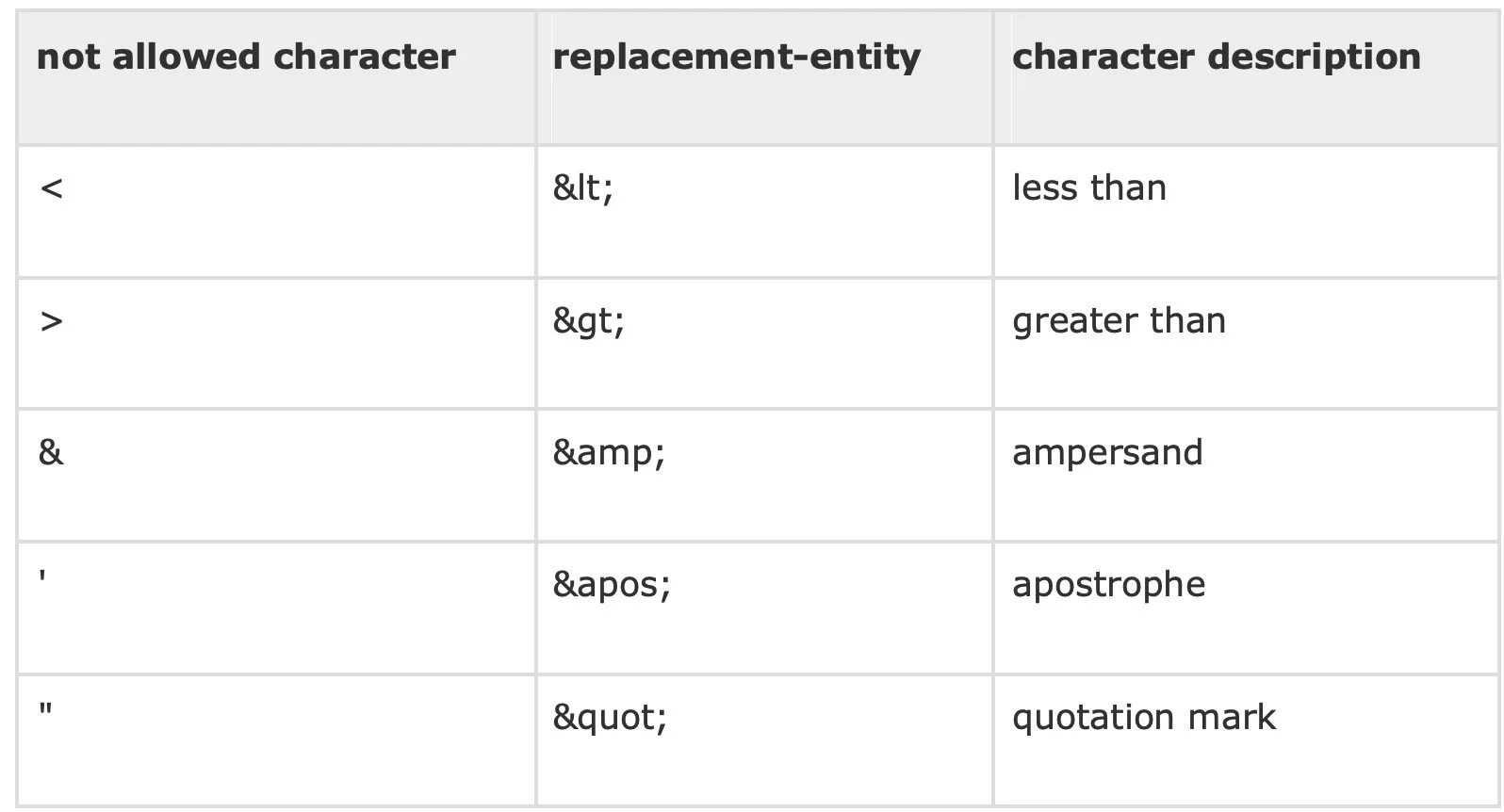

Sometimes references are used so the computer knows the difference between markup language and actual data. For example, if the text you want to display has characters used in markup language, like < or & or >, you have to replace those characters with entity references so as not to confuse the parser.

Another type of reference is the character reference. This is used when you need to access a character that is not easily accessible on your keyboard, e.g. ©, ™, or °.

Copyright ©

Decimal: ©

Hexadecimal: ©

Trademark ™

Decimal: ™

Hexadecimal: ™

Degree °

Decimal: °

Hexadecimal: °

So, if you wanted to display: Water boils at 100°C

In XML, you'd write: <note>Water boils at°C</note>

Why can character references be written in decimal or hexadecimal abbreviations?

With certain abbreviations, it’s easier to use the decimal abbreviation because of their ubiquity. Some characters are used so often, their decimal abbreviation are short, so it’s convent to type © in place of ©.

For other abbreviations, emojis for example, have such long decimal references that it’s easier to use the hexadecimal reference.

Prolog

The prolog is the section that comes before the root element in an XML document.

The prolog has three parts:

Declaration

Processing Instructions

Document Type Definition

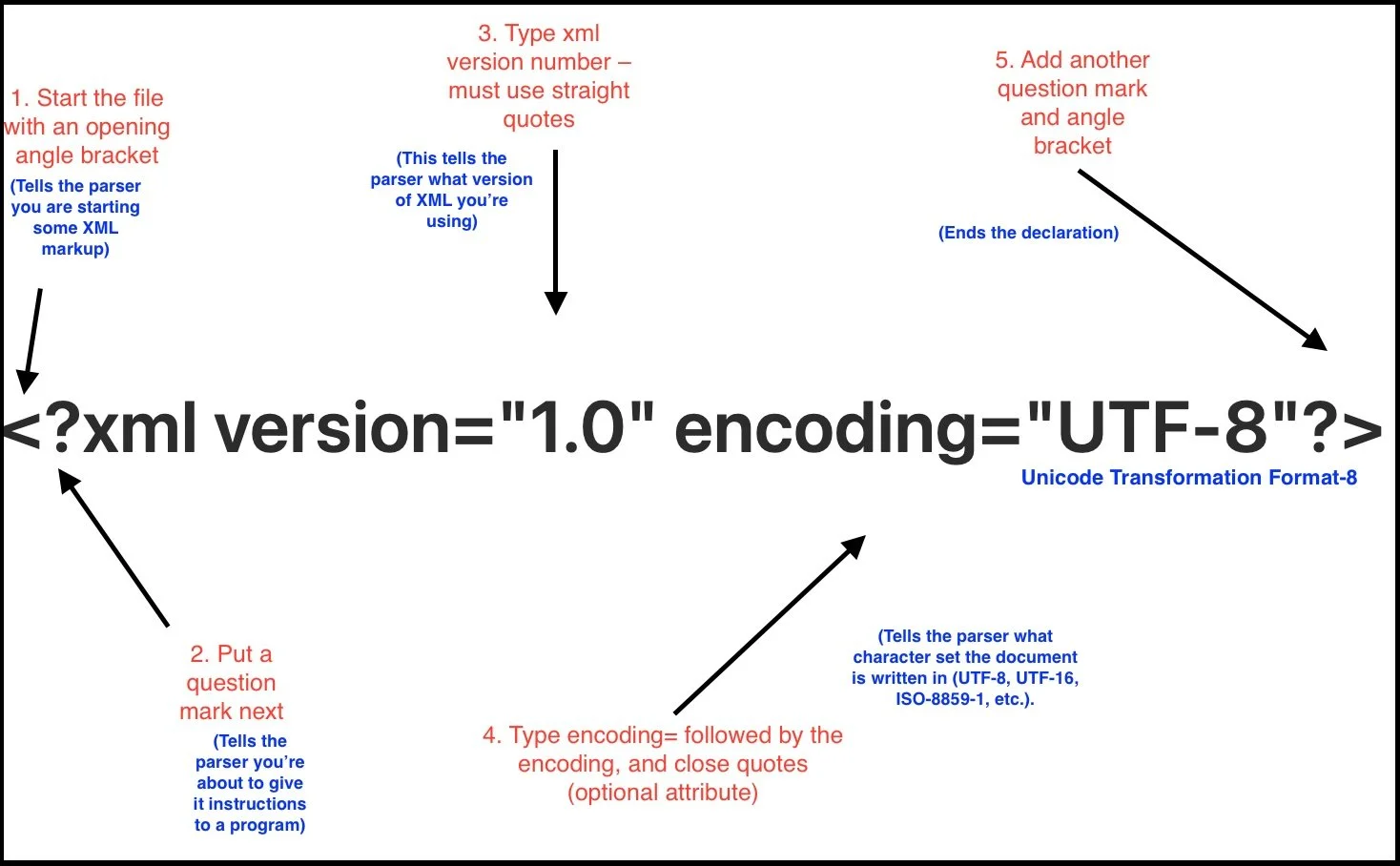

Declaration

The purpose of an XML declaration is to give the parser (a computer program designed to read the XML document) a set of instructions for how to interpret the document it’s about to parse.

Although a declaration is optional in an XML, document it is highly recommended

Parts of a Declaration Explained:

Processing Instructions

A processing instruction gives information to the application that’s processing the XML, not to the XML parser itself.

Full Prolog Example

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> (Declaration)

<?xml-stylesheet type="text/xsl" href="x.xsl"?> (Processing instruction)

<!DOCTYPE note SYSTEM "note.dtd"> <!-- (DOCTYPE)

<note>

<to>James</to>

</note>

Conclusion

I hope you have found this XML guide to be helpful in your aims of learning this markup language better.

Like with anything, experience and repetition of writing in XML will help more than any reading can do.

Now that you understand the meaning behind all of the jargon, it should be easier to teach yourself even more about XML with the help of other internet and print resources.